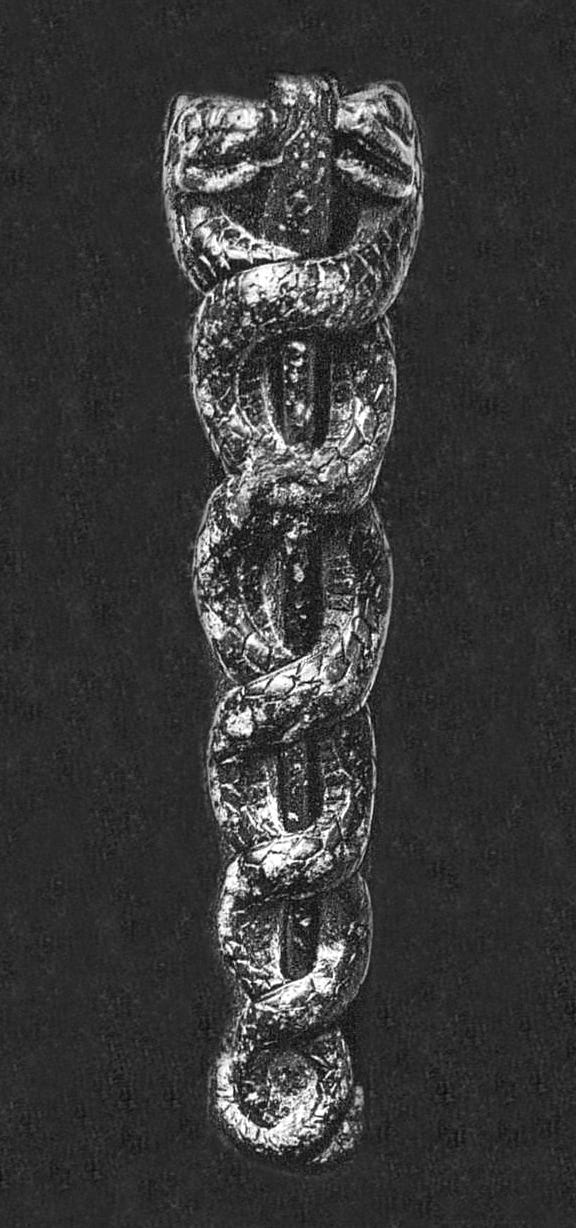

“The best way to control the opposition is to lead it ourselves!” This line is attributed to Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924), the revolutionary founder of Soviet Russia. Whether or not he actually spoke those words is unclear; regardless, the sentiment succinctly expresses the overdetermined and suffocating nature of a totalitarian system: even those ostensibly opposed to the government or party in power are, in fact, tools of the system—and otherwise wouldn't be allowed to exist. This galling quotation has functioned as a watchword for conservatives for at least the last half century. Here, they contend, the most compromising or compromised elements of the Right are installed as leaders; their role is ultimately to blunt, neuter, or obscure the "true" opposition. This might sound like conspiracy-tinged rhetoric, but the Leninist maxim very much describes a recurring phenomenon. It is deeply mistaken, however, to consider it uniquely totalitarian, Marxist, or even especially modern. Rather, it is ancient. Its best symbolic representation is that of the caduceus. We first find this image in Sumer with the symbol of the god Ningishzida.

The caduceus, particularly as it is refined in Greco-Roman symbolism, is a wand or staff entwined with two opposing serpents facing each other. This is understood as Mercury’s shepherd staff, by which he leads the flock. The caduceus is also a wand that hypnotizes. When Mercury spins the caduceus, it becomes enthralling: his followers fixates on it and can't look away. Entertained and pacified, the flock is at his command. That Mercury is the one wielding the device is of great importance. Mercury, the deceiver, traveler, and merchant, is a proto-Jewish figure standing in vivid contrast to Apollo, the god of truth. Indeed, in one popular myth, a young Mercury steals Apollo's herd of cattle—that is, becomes the shepherd of his flock—and after being caught red-handed continues to dissemble before Zeus. That Mercury is the merchant, and the caduceus, a symbol of commerce, may point to the financial nature of this phenomenon. One myth describing the caduceus’ origin relays that Mercury encountered two fighting serpents along his way. Once he adorned his staff with them, the myth implies, the contest between the two became a kind of simulation, a show meant only to entrance. Another myth describes the serpents of the caduceus as derived from a mating pair. In modern context, we imagine the rigged wrestling matches between Fox News and CNN, Republicans and Democrats, the Red Sox and Yankees, Left and Right—all in opposition but also in love with one another. We might consider the symbol of the Ouroboros, which depicts a serpent eating its own tail—thus fighting itself—as a related, if not synonymous, figure.

The real poles of opposition in this world are not between the two serpents of the caduceus but between Mercury and Apollo, between the non-Aryan underworld, which Mercury leads, and Apollo’s protective enclosure. It is the audience of the enthralling caduceus—the human flock—over which Apollo and Mercury vie. It is important to remember as well the serpents of the caduceus evoke Bacchus. In Mercury’s hands, there appears the suggestion of Jews as involved in the deliberate promotion of degeneracy, which even a generous Nietzsche admitted. Mercury, like Bacchus, also becomes “the Vintner.” Yet here, with the caduceus, we find two serpents, hence two, ostensibly oppositional forms of degeneracy. To wit, one is forced to “pick his poison.”

The serpents themselves are also likely drawn from the medicinal cults of the ancient world, whereby snake venom was used on patients as therapy (in truth, as opiates). Though the caduceus is frequently used as a symbol of medicine today, this application is mistaken. The proper symbol of this profession is the rod of Asclepius, a supposed healer, with only a single serpent entwining his staff.1 Here, too, the symbolism is revealing. With just enough poison, an analgesic or euphoric sensation is produced. With too much poison, sickness or death will follow. Likewise, as with any toxin or narcotic, through continued use, one builds up a tolerance; sustained use is numbing and, in the end, destroying. Hence, there is something especially unpleasant about the mistaken use of the caduceus in medical symbolism, which, again, is understood as a staff representing commerce. Those incensed by the opioid crisis facing modern Americans will find this symbol especially upsetting, if apropos.

Likewise, with the first Jewish Christians—these Hermes Poimandres or “Shepherd’s of Men”—we find “physicians” selling a cure for the poison they also inject. This technique is described explicitly in the Hebrew Bible. In Numbers 21:8, Moses’ fiery serpent is created as a “cure” for serpents that Yahweh had previously sent among the people of Israel to poison them. We might surmise that the first “serpents” might have been the vines of Bacchus: alcoholism, vice, and so forth. Yahweh stays sober while he sickens; he creates a "problem" and then sells “the cure," one that allows him to be feared, followed, and adored. Likewise, Christian morality emerges as a “cure” for degeneracy. It is the method of Mercury, the deceiver and psychopomp, to first put before the audience every tragedy and anxiety, before placing before him every easy, mollifying, false, feel-good solution. We see this in the “problem” of a personal death and the “solution” of an afterlife. We see this in the “problem” of hierarchy and the “solution” of democracy. The “problem” of racism and the “solution” of multiculturalism. The “problem” of sexism and the “solution” of androgyny. Christian "redemption" is itself based on the "problem" of Original Sin—Adam's curse, which no man can escape—and the "solution" of salvation through Jesus' sacrifice. All these examples are caducean oppositions; the "problems" are as synthetic as the "cures."

Between "problem" and "solution" lie some convincing, persuading, and seducing. Some race to the solution; others resist it instinctively, and must be coaxed (or threatened) to accept it. Thus two camps form organically: the “early adopters” and the “slow learners,” the "liberals" and the "conservatives." The name “liberal" is itself a reference to Liber Pater or Bacchus. Christianity posits itself on the opposite side of Dionysius, and yet Christ is “the vine” and the man who turns water into wine. In other words, he is Dionysius sublimated, the serpent in dove’s clothing.

For the purposes of clarity, let us incorporate the familiar terminology appearing in the Assemblée nationale during the French Revolution: Left and Right. We will consider the serpent of the “Right" closest to Apollo’s enclosure, though he remains false. The “Left,” on the other hand, has no compunction in identifying itself with Bacchus and the underworld, often sublimated as the "underclass" or "wretched of the earth." In every instance the “right” head should be understood as transitional, as a mask of Mercury, the shepherd leading the flock, ever so gradually, toward the “left” and the world là-bas.

After the ascent of Christianity, at some point, Christ became the "Right," the slower of two poisons, whereas Satan and decadence defined the "Left." This division would quickly manifest itself more subtlety and complexly in schisms within the Church itself. Eventually, we see Catholicism and Protestantism, then Christianity and capitalism, then back ‘round again to capitalism and communism, conservatism and liberalism, and so on. Such is the twirling caduceus. On a deeper level, we see every synthetic-opposition that keeps the flock from the Apollonian enclosure: the Pharisee versus Christ, both with the same promise; Christianity versus Islam, both derived from Judaism and possessed of the same goal; "patriarchal” Christian versus the liberal "feminists," man versus woman, publicly airing our grievances.

The caducean also conceals the reality that the followers of Judaism are, ultimately, a monolithic block (qua Hermes the “stone"). To the extent that the caducean struggle is real, it is a competition over resources and power between two Jewish-led factions. The caducean also describes a necessary “division of labor”: the brighter lights are destined for the leftist vanguard, while the dimmer bulbs are relegated to conservatism. Likewise it conceals individual hypocrisy, which could than be extrapolated to group hypocrisy: "Leadership and identity for me; multiculturalism and dissolution for thee." One faction ostensibly segregates from another, so that individuals on both sides may avoid any hint of hypocrisy or inconsistency. While it may be the case that most Jews are "on the left" and in favor of multiculturalism, the development of “two opposing sides" creates the impression of a divided Jewry. It lends credibility to persons in each camp who are, ostensibly, principled. Yet the conflict is obviously theater, a “caducean twirl,” developed to create the impression of a self-regulating Jewry, one that doesn’t require external input, which if too meaningful is hastily deemed “anti-Semitic.” Critique remains “in house,” where punches can be pulled and the outcome, preordained, while no actual contender is allowed to enter the ring. Here the relation between Aryan and Jew is very much like that between shepherd and sheep or parent and child. Parents, naturally, make the decisions in the family, not the children. Jews are, in this way, monolithic on the only question that matters: Judaism must continue and chart its own course, with no input from outside; otherwise it is endangered.

From this perspective, much can be learned, if not imitated exactly. The "two faces" of the Aryan are both honest: one is the gentle, reasonable, and brilliant Apollo; the other, the warlike, brutal, and quick-tempered Mars. There is, of course, good reason to prefer Apollo and keep Mars at bay; it is the former who defines civilization, and the latter who can destroy everything if not tamed. In the end, both are equals by necessity, and they define and set off one another. Each can be plausibly presented to subdue an adversary; when they are combined in one person, he is invincible. Whatever the case, the motto of any group wielding a caduceus is this: "Things will go our way, one way or the other."

We will find it encouraging to remember, as Karl Kerenyi points out, that in the earliest tales of Apollo’s battle with Python—and his establishment of the Temple at Delphi—two serpents are indicated, a female named Delphyne and a male named Typhon.2 Thus Apollo triumphs not merely over a single serpent; he overcomes the caduceus itself. Nevertheless, we would be wise to remember: serpents always come in pairs.

Asclepius himself, though officially the son of Apollo, was born of the unfaithful lover Coronis (“raven”) and perhaps should be understood as Semitic. Indeed, the raven, after which she is named, is a symbol of death, darkness, and admixture. This is revealed especially in the Hebrew word ereb/oreb (ערב), meaning “raven,” “to mix,” “to grow dark,” “evening,” “mixture, mixed company,” “foreign people,” “Arabia.” Likewise, the Semitic element of earthly fire features centrally in Asclepius’ birth, where he is understood as having been rescued from his mother as she was consumed on a pyre. In a sense, he was “fire born.”

Karl Kerényi, The Gods of the Greeks (London: Thames and Hudson, 1974).

If this is a preview of the book, then I'll be buying two copies. One for myself and one for someone with ears willing to hear.